By Sabella Jane and Nadya Theresia

In the last article, we have reviewed history and read how the violence and exile suffered by Jews millennia ago led to the current statelessness of millions of Palestinian Arabs. The issue surrounding Israel and Palestine, at its core, concerns the colliding rights to living space between two peoples in Palestine: the Jews and the Arabs.

But the massive demographic change as well as the co-existence of two different social systems were not the only causes of escalating confrontations between Arabs and Jews. Another, perhaps more consequential reason is the fact that Britain made two antithetical promises to Jews and Arab as regards Palestine. On the one hand, Britain promised Palestine to the Arabs through the 1915-1916 Hussein-McMahon Correspondence to garner support against the Turks in World War I. On the other hand, Britain promised the “establishment in Palestine of a national home for Jews” through the 1917 Balfour Declaration. The resulting clash of rights is the substantially complex core of the modern-day conflicts between Israel and Palestine.

The Right to Self-Determination

The right to self-determination is recognised as a crucial element in contemporary international law. This collective right is embodied in the UN Charter and two prominent human rights treaties, namely the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (“ICESCR”). Article 1 of both treaties describe the right to self-determination as “the right of all people to freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.” Essentially, and perhaps, more broadly, this right enables peoples to freely determine their own destiny.

Although the right to self-determination was first intended for emancipation of colonised nations, it no longer serves that purpose alone. As international law progresses, the time of conquering powers in world history eventually fades. The French Revolution in the late 18th century shifted the orientation of government power. Democracy, a system operating on the basis of the consent of the governed and the sovereignty of the people, became the idealised concept of government, and so individual freedom expands and applies to the community as well. This ideology is upheld by countries like the United States and United Kingdom, believing that the right of self-determination does not apply to only colonised nations, non-self governing territories, trust territories, or zones under military occupation, but also to a territory which is geographically distinct, and ethnically or culturally diverse from the remainder of the territory of the administering Power.

The Jews are no stranger to the right to self-determination. History shows us that the millennia’ worth of persecutions befalling Jews has led them to believe that their safety would only be achieved in their own Jewish State. This belief is the foundation of Zionism, the Jewish national movement for self-determination, whose goal is to establish a Jewish national homeland in Palestine, formerly the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah, original homeland of the Jews before the Babylonian Diaspora. Jews were repeatedly exiled into foreign lands, where as minorities they faced mass hatred, violence, forced conversions, and massacres like no other religion. In that sense, years of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism denies Jews’ right to self-determination. But even when Israel was finally able to declare independence in 1948, their exercise of this right was not without difficulty, as the fight over living space between Jews and Arabs immediately ensued and would continue over future decades. A multitude of reasons rise as possible explanations behind the fights that followed, but perhaps most notable of all is Britain’s unclear and contradictory promises to Arab and the Jews in the form of the 1915-1916 Hussein-McMahon Correspondences and the 1917 Balfour Declaration.

Arab’s Demand for Territory: the Hussein-McMahon Correspondences

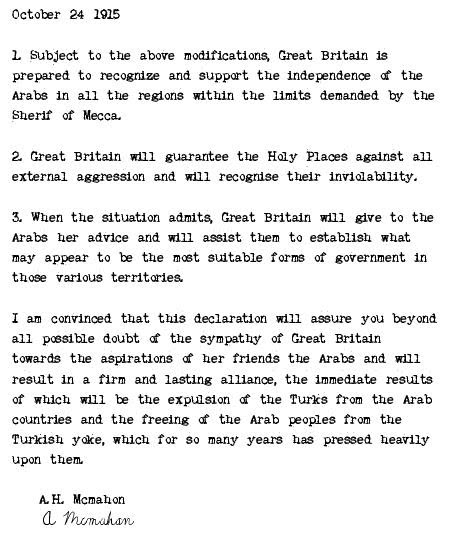

Through a series of letters in 1915-1916 between Sharif of Mecca Hussein ibn Ali and British diplomat Sir Henry McMahon, Arab requested British support for the independence of a series of territory desideratum from the Turks, and Britain gave that support. The exact wording of second letter, penned by McMahon in response to Arab’s request for support in the correspondence reads, “[…] we confirm to you the terms of Lord Kitchener’s message, […] which was stated clearly our desire for the independence of Arabia and its inhabitants, together with our approval of the Arab Khalifate when it should be proclaimed.”

One arising issue is differing understandings of the word ‘independence’ by Britain and Arab. While ‘independence’ was understood by Britain as to exclusively mean the freeing of Arab states from the Turks, Arab, on the other hand, aimed to form an independent unified Arab State. Arab nationalists rely on the shared cultural, language, and religious background as a reason to unify the Arab states to relive Arab’s former glory under the Prophet Mohammed. This was also the wish of Hussein ibn Ali, direct descendant of the Prophet, who wanted to reestablish the past renown of his race, family, and religion by becoming the King of the Arabs and Khalif of all Mohammedans.

But the fight over living space does not directly stem back to the issue of a unified Arab State, but rather concerning territories. In his first letter Hussein set out a demand for British recognition of independence of a series of territories from the Turks, including Palestine. Britain was reluctant to agree to this demand, and McMahon’s response was that it was premature to talk of limits and boundaries so long as the Turks were still in effective occupation. Another reason explaining McMahon’s reluctance to recognise independence to the territories set forth in Hussein’s first letter was because Syrian Arabs were lending their assistance to the German and the Turks instead. But this reluctance soon subsided when Al Faruqi, prominent member of the Young Arab secret society, arrived in 1915 Cairo. Al-Faruqi claimed that Young Arabs had massive influence in Syria and Mesopotamia, and revealed under interrogation that Germans and Turks had approached them to promise what Britain was reluctant to give them. He also claimed that if Britain did not reply favorably within a few weeks, the Young Arabs would side with Germany and Turkey to “secure the best terms they could.”

Evidence gives little credence to Al-Faruqi’s claims. For one, Ottoman’s Djemal Pasha’s autocratic rule in Syria and Palestine provided no urgency for Turks to recognise Arab States’ independence. German records also show that Dr. Prüffer, Consul-General in Damascus, reported that the anti-Turk movement was weakening as the bulk of the Arab population sided with Turkey. Prüffer’s successor, Dr. Loytved-Hardegg, even stated that “no rebellion need be feared in Syria. The Syrians are shopkeepers but no[t] warriors. They are little gifted for the profession of revolutionaries.” It is then reasonable to assume that Al-Faruqi’s statements to Britain were measured assertions aimed to strengthen Arab’s bargaining position as regards the list of territory demands in Hussein’s first letter. Seemingly triumphant for the Arabs, the reality was that it did exactly that.

A Hasty Conclusion, Ambiguous Diction, and Contradictory Understandings

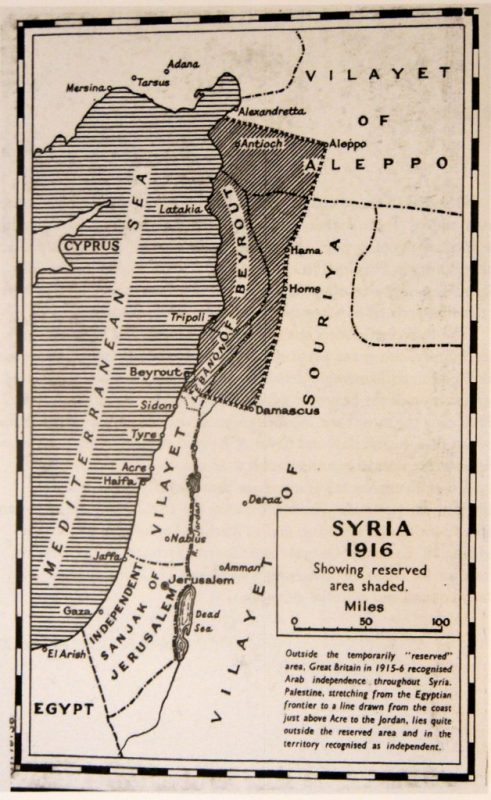

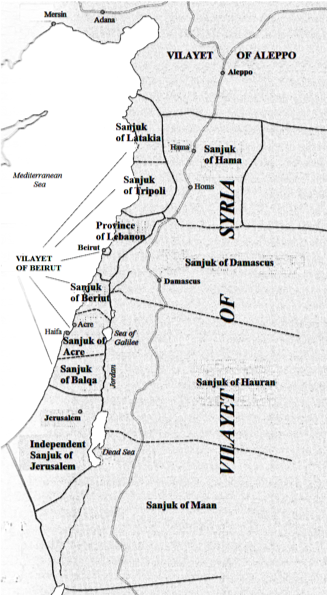

Believing Al-Faruqi, Britain was eager not to alienate the Arabs’ loyalty. In the fourth letter dated 24 October 1915, McMahon, perhaps too hastily, agreed to Hussein’s territory desideratum with few reservations, stating that “the two districts of Mersina and Alexandretta and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab, and should be excluded from the limits demanded.” This rushed decision effectively resulted in contradictory understandings between Britain and Arab over whether Palestine was recognised by Britain as an Arab State.

The October 1915 letter was sent by McMahon despite forewarning by Britain’s Foreign Minister Sir Edward Grey, who suspected that Al-Faruqi’s statement had an ulterior motive and, therefore, was not forthcoming. Against this advice, McMahon sent the letter without further consultation, effectively cementing the Arabs’ view that since Palestine was not specifically mentioned in this reservation, it followed that Palestine was ipso facto included in the territory recognised by Britain for Arab’s independence.

Following what historian Isaiah Friedman called Britain’s ‘standing embarrassment’ in his hasty reply, McMahon has on numerous occasions denied that their meaning of support for Arab States’ independence under the Hussein-McMahon Correspondences extended to the unification of Arabia. Sir Gilbert Clayton, Britain’s Director of Military Intelligence in Cairo affirmed in his private letters that Britain’s intention was only to “work towards the maintenance of the status quo ante bellum, merely eliminating Turkish domination from Arabia.” Britain seemingly did not anticipate the potential confusion as Director of British Intelligence in Cairo Gilbert Clayton wrote in one of his letters to British politician Ronald Wingate, “luckily we have been very careful indeed to commit ourselves to nothing whatsoever.”

McMahon later clarified in 1937, when the conflict over living space between Jews and Arabs were already ensuing, that Britain did not intend to recognise Palestine as an independent Arab State despite his negligence to mention Palestine in his reservation. McMahon and Clayton again denied in 1939 that Palestine was included within their meaning in the territories they recognised for Arab independence. In turn, Arab contended that this clarification of personal intent by McMahon and Clayton were of no importance, since the pledge to Hussein was not theirs as individuals but rather as instruments of the British government.

Britain argued that the reservation, which read, “the two districts of Mersina and Alexandretta and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab, and should be excluded from the limits demanded,” also included the vilayet of Beirut and Sanjaq of Jerusalem, and therefore, Palestine. Moreover, there were approximately 100.000 Jews in Palestine at the time, which renders Palestine as not ‘purely Arab’ as well, and thus, should be included within the meaning of McMahon’s reservation. But Britain was not oblivious to its own negligence to use clear diction. The British representative in the 1939 Conferences on Palestine acknowledged that Palestine was indeed included in Hussein’s territory desideratum in the first letter, but also contended that McMahon’s reservations excluded Palestine from those territories although admittedly the wording of the reservation was “not so specific and unmistakable as it was thought to be at the time.”

The aftermath of McMahon’s decision was chaotic at the very least. Hussein’s promise that the Arabs would fight the Turks in exchange for arms and money, which the British provided, was not executed satisfactorily. The truth was that Palestinian Arabs never intended to rebel against the Turks, as the Arab population in general welcomed the Ottoman Empire’s rule where they enjoyed equality of rights. Arab troops in the Ottoman army even remained loyal to the Empire, and it was in fact Hussein’s own people who bore the brunt of the rebellion against Turks. Though not without advantages, the rebellion achieved far less than what Britain had expected, and as Friedman concisely described it, “if any party remained in debt towards the other, it was rather the Arab to the British than vice versa.”

Even before the concept of self-determination emerged in international law and relations in the UN Charter, Arab viewed that they had British assurance of their independence in the form of the Hussein-McMahon Correspondences, and that this promised right to independence as a unified Arab State was directly denied by the Balfour Declaration.

The Balfour Declaration: Britain’s Promise to the Jews

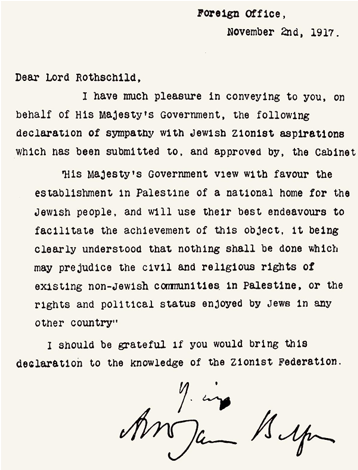

Like light at the end of the tunnel, the path towards Jewish self-determination was initiated to the Jews by Britain through the 1917 Balfour Declaration, concluded by Britain’s first Jewish Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. Influenced by his belief in Zionism and the hope that favoring Jews would gain support from neutral States in the Allied powers like the United States and Russia, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917.

The Declaration essentially facilitated the Jews’ right to self-determination in the modern sense, as it was Britain’s acknowledgement for Jews to create their own State in Palestine. Britain explicitly guaranteed in the letter exchange between British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour and Zionist politician Lionel Walter Rothschild that they will establish a national home for Jews in Palestine, and that Britain “…will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object.” But this support towards the establishment of a Jewish national home does not “prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

After World War I, the Allies convened in San Remo, Italy in 1920 to discuss a peace treaty with Turkey as the Ottoman Empire’s successor. There, the Allies assigned to Britain the mandate over Palestine on both sides of the Jordan River, and the responsibility of putting the Balfour Declaration into effect. Later on in 1922, the League of Nations formally designated Britain as Palestine’s mandatory Power.

Growing Numbers and the Fight for Living Space

Britain’s victory in World War I gave effect to both the Hussein-McMahon Correspondences and the Balfour Declaration. As a result, a massive influx of Jews migrated into Palestine, a change never well-received by existing Arabs in Palestine because of the colossal change in demographic that followed. In under 2 decades from 1922-1945, the population in Palestine more than doubled from 700,000 to 1,800,000 inhabitants, with the number of Arabs doubling while the Jewish population grew tenfold. This increase led to repudiation from Palestinian Arabs in the form of violent confrontations and riots against Jews, resulting in hundreds of lives lost throughout the 1920s-1930s.

Scholars have tried to understand why xenophobia against Jews in particular was so powerful throughout centuries. Some scholars have concluded that there is a causal link between extreme pride in one’s own nationalistic, racial, or religious identity and the emergence of xenophobia in a society, though as we have read in the previous article with the example of brit milah (circumcision) and how the Romans banned the practice for Jews, repression of a foreign culture would only increase its significance to the people practicing them. Once again, religious exclusivism, or any excessive fanatic belief, plays a role in the cultivation of hate.

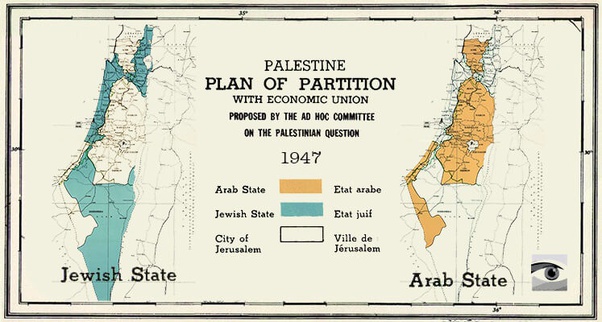

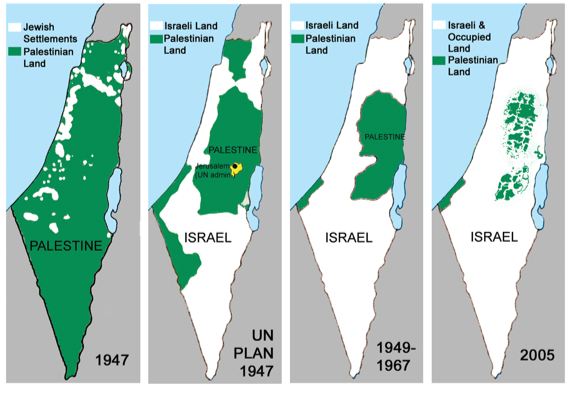

War-weary Britain finally had enough of the violent confrontation between Arabs and Jews, especially since, to some extent, the British Army also bore the brunt of these violence. The King David Hotel bombing in 1946 triggered Britain to refer the Palestine issue to the newly-formed United Nations, which subsequently birthed the partition plan over Palestine and divided Palestine into three parts, one each for Jews and Arabs, and separated Jerusalem as an international zone.

Unwittingly, an Eye for an Eye: Israel’s Denial of the Palestinians’ Right to Return

After enduring millennia on the receiving end of exile and violence wherever they went, Jews finally declared independence as Israel in 1948. The Jews finally, after only being able to dream of self-determination for so long, became an independent nation with the capability to determine their own fate. But as we have learned through history, despite Zionism stemming from centuries of statelessness and persecution against Jews, Israel today is very ironically making it harder for Palestinian Arabs to exercise their right to self-determination.

The Arabs’ disapproval of the UN partition plan entailed legal uncertainty of their statehood. Decades spent fighting with Israel further devastated the Palestinian Arabs, and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians became refugees after their massive panic and flight from their homes in the 1948 Palestinian Exodus. These stateless Palestinians dispersed to Israel and neighbouring countries.

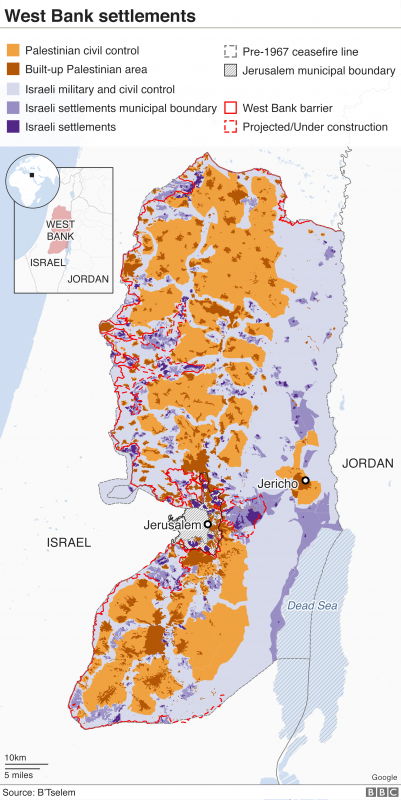

After the 1967 Third Arab-Israeli War, Israelis started building settlements in the West Bank, originally allocated to the Arab State in the UN Partition Plan. UN Special Rapporteur Michael Lynk has stated that “for Israel, the settlements serve two related purposes. One is to guarantee that the occupied territory will remain under Israeli control in perpetuity. The second purpose is to ensure that there will never be a genuine Palestinian State.” The practice of settler implantation is prohibited under the Fourth Geneva Convention, and is categorised as a war crime by the international community under Article 8 of the Rome Statute, founding Statute of the International Criminal Court.

The war had dispersed almost half a million Palestinian Arabs out of their homes as Israel’s control over Palestinian territory expanded. By 1970, three million Palestinian Arabs were dispersed to neighboring Arab States and Israel, with a portion living in the borders of Palestine as refugees. By 2019, Amnesty International documented 750.000 Palestinian Arabs in West Bank and 1.26 million in the Gaza Strip, now living as refugees amidst bombings and the growing conflict between two entities.

Israel to this day refuses to grant these refugees their right to return to what is now occupied Palestinian territory, and instead believe that the refugees should resettle in Arab States. Israel bases their refusal on their contention that the refugees should only return to Palestine once peace is achieved, or else the “peaceful life amongst neighbours” envisioned in the 1948 UNGA Resolution 194 (III) granting Palestinian Arabs the right to return would not be achieved. Moreover, Israel also considered the fact that should Palestinian Arabs be repatriated, the refugees would be placed “under the rule of a Government which, while committed to an enlightened minority policy, was not akin to those Arabs in language, culture, religion or social or economic institutions.” Despite these considerations, international law has repeatedly, and rightly, sided with the displaced Palestinian Arabs.

The right to enter one’s own country itself is recognised as a human right under the ICCPR and the ICESCR and applies to a large group of displaced people. Most specifically, the Palestinians’ right to return has been endorsed by the UN General Assembly. In 1974 and again in 2021, the UN recognised that these displaced Palestinians were entitled to the “inalienable, permanent and unqualified right of the Palestinian people to self-determination, including their right to live in freedom, justice and dignity and the right to their independent State of Palestine.” Though UNGA Resolutions are regarded as soft law, Israel is a member State to the ICCPR and the ICESCR with no reservations concerning the right to self-determination.

Assassinated Attempt at Peace: the Oslo Accords

An attempt for peace was made in 1993 when the Oslo I Peace Accord was signed by representatives from Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (“PLO”), a militant Palestinian national movement which sought to create a Palestinian State, and the Oslo II Accord signed in 1995.

On paper, the Accords was the poster-child for wishful peace between Israel and Palestine as it set out to actualise the Palestinians’ self-determination. For many, the Accords were the manifestation of new-found hope that peace would be achieved, as Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s Prime Minister, formally acknowledged the PLO as representatives of the Palestinians. In return, the PLO formally recognised Israel as a State, a statehood previously immediately and violently challenged since Israel declared independence in 1948. The Oslo Accords set out an interim period of five years, during which Israel would withdraw from Jericho, the Gaza Strip and West Bank. The Accords also sought out to establish a ‘Palestinian Interim Self-Government Authority’ and Israel allowed the Palestinians limited self-governance in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, previously occupied by Israel, along with the forming of a Palestinian Legislative Council. Amongst other obligations and rights, a transfer of powers from Israel and the establishment of a Palestinian police force was also included in the Accords. The Palestinian National Authority was later established in 1994 as Palestine’s transitional government. Yasser Arafat, founder of the PLO and witness to the signing of the Oslo Accords, was assigned as head of the Palestinian Authority and the process of establishing an autonomous rule for Palestine began.

But the Oslo Accords were opposed by both Israelis and Palestinians. Yitzhak Rabin was dubbed a traitor by Israelis in the West Bank for having negotiated the Accords. Nationalist movements such as the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine also opposed the Accords for not making clear any intention to establish a Palestinian State. In their view, Israel only offered autonomy, and “thereby freeing itself of the economic burden of the Palestinian population, while granting itself overall control and keeping all the Jewish settlements with West Bank and Gaza.”

Palestinians’ reactions to the Accords were not exactly welcoming, either. Terror attacks inside Israel and the occupied territories increased, which eventually dwindled support for the Accords. Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said even nicknamed the Accords as the Palestinian surrender, or the ‘Palestinian Versailles’ since it effectively gave away 78% of Palestinian territory to the Israel. Hamas, a Palestinian militant organisation controlling Gaza, stated that Yasser Arafat has sold the Palestinian cause to the Zionist by negotiating and signing the Oslo Accord. This organisation also intensified bombing, kidnapping, and suicide operations as a response to the Accords. The peak of this discord was in 1995 when Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a devout law student who justified his act of murder because Rabin wanted “to give our country to the Arabs.”

There are abundant opinions on why the Accords failed, but the Peace Accords are now a dead agreement. Israeli’s illegal settlement continues to expand in the West Bank until today. This negatively impacts Palestinians in the occupied Palestinian territory, as seizure of land for construction of settlement buildings and future expansion has progressively diminished space available for adequate housing, basic infrastructure, and services needed for the livelihood of Palestinians.

It is true that in the course of exercising their right to self-determination and attaining independence as a nation, Jews experienced tumultuous hardships. Today, as was done to them millennia ago, Israel has deprived another nation of their right to self-determination. Although the Oslo Accords were concluded between them, each party’s entitlement for the land has rendered the Accords useless, and the fight over living space continues until today.

We sincerely thank Dr. Tristam Pascal Moeliono, S.H., M.H., LL.M., Adrianus Adityo Vito Ramon, S.H., LL.M. (Adv.), and Anna Anindita Nur Pustika, S.H., M.H. for the guidance they have provided as faculty advisors for this series.This is the second article in PILS’ article series concerning the issue of Israel and Palestine. The next article will cover the Palestinian Wall and Israel’s illegal settlements.