Writers: Sabella Jane, Evan Jonathan, Nadya Theresia

Editors: Nadya Theresia, Michelle Lydia

Every single action in the universe will, inevitably, produce a reaction. Perhaps this is the most befitting phrase to describe the situation surrounding Israel and Palestine. The conversation about this issue will inevitably lead us to converse about religion, and with one look at history it is undeniable that a correlation exists between the persecutions suffered by Jews since millennia ago and the current statelessness of Palestinian Arabs from the Palestinian Exodus. The Jews’ yearning for a State of their own is fueled by their exigency to rightfully break free from tyranny, and it is this need that birthed Zionism. But that same utopic dream of safety threatens the security of others years later in the Palestinian Exodus. Thousands of Palestinian Arabs remain displaced and stateless to this day.

Ancient Babylonia and the First Jewish Diaspora

Historically, the issue began when Jews were forcibly dispersed out of their own homeland thousands of years ago. This is known as the Jewish Diaspora. The Babylonian Diaspora in particular is one of the most notable Jewish Diaspora in history, as this is the first instance where Jews were driven out of their homes by conquering powers.

Subsequent to King Solomon’s death, the land he ruled was divided into the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah or commonly known as Judea. These territories make up what would later be called as Mandatory Palestine by the United Nations before Israel declared independence in 1948. But millennia before that in 722 BCE, the Assyrians invaded the Kingdom of Israel, and the Jewish population priorly living there fled to the Kingdom of Judah with Jerusalem as its capital. It is this early in history that the dispersion started and Jews lost their homes.

Nearly a century after the invasion, the Assyrian Empire was conquered by Nebuchadnezzar II, the King of Babylon. Following this conquest, most of Assyrian provinces fell into the Babylonians’ hands, including the Kingdom of Israel. The Kingdom of Judah in 586 BCE would later meet the same fate. In particular, Nebuchadnezzar II burned the Kingdom of Israel along with the Jewish Temple Solomon had built, which was particularly significant for Jews since it originally housed the two tablets of the Ten Commandments. As it was the standard Mesopotamian practice to deport the existing population in a territory after conquest by its king, Nebuchadnezzar II did so to the Jews from Judea to Babylon. This is what we now know as the Babylonian Diaspora.

The Babylonian Captivity forged a new identity for exiled Jews. They creatively repositioned their view of the exile and reflected inwards to try and understand the hardship they were enduring. In particular, they held themselves responsible for corrupt worship practices and attributed the exile to this sin as the reason of their suffering. And so, the focus shifted to searching for salvation and rebuilding their community in Babylon. We see recollection of this exile and restoration in the form of biblical allegories, particularly in Ezekiel’s illustration in the Old Testament by painting Nebuchadnezzar II as the ‘great eagle king’ who exiled the Jews to replant them in “fertile soil, a plant by abundant waters, he set it like a willow twig.” The Bible’s recollection tells us that the exile did not falter the Jews’ faith. They were burnt and emerged unscathed in defense of their religion. Sadly it is this rectitude that would elicit hate throughout the next centuries.

In the Absence of an Independent Nation: the Persian Empire and the Greeks

The Persians conquered Babylonian territory in 538 BCE. Persia’s King, Cyrus the Great, decreed freedom to a subjugated nation and brought Jews back from Babylonia into Judea, where they rebuilt the Temple of Solomon, known as the Second Temple, which holds great significance for Jews. Although the Jews were free to go back to Jerusalem, they were no longer an independent nation as Jerusalem and the areas priorly the Kingdom of Judah had become mere provinces in the Persian Empire.

In 334 BCE, Greece’s Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire. Upon his death in 323 BCE, the Persian Empire was divided amongst his generals. One of his generals, Seleucus I Nicator, formed the Seleucid Empire and gained control of Judea in 204 BCE. This is where Jews faced religious and cultural decimation, as Antiochus IV sought political dominance and stripped away any traces of Judaism in an effort to eliminate the faith altogether. Jews were forcefully Hellenised and made to adopt the Greek way of life under Antiochus IV’s rule. One practice that stood out was his use of political connections to build a gymnasium in the middle of a Jewish temple, effectively asserting dominance over the Jewish community. Antiochus IV also made it mandatory for all males to enter the gymnasium without clothing, a reflection of the Hellenistic idea of masculinity, but a practice banned in the Hebrew faith.

A rift then grew between devout Jews and Hellenised Jews, which led to a rebellion from devout Jews against the Seleucid Empire in 167 BCE. Led by a priest named Mattathias, the revolt was a success. Jews gained control of the whole of Judea and subsequently constructed the Hasmonean Dynasty, a Jewish independent rule, in what used to be Seleucid Empire territory.

The Roman Empire and the Mistreatment of Jews

The fall of the Seleucid Empire brought about the Romans as the next great power in the region. Judea fell under the direct administration of the Romans and the Jewish Diaspora grew in number. The Hasmonean King that had settled in Judea was only granted limited authority under the Roman governor of Damascus.

The people of Judea resisted this Roman occupation and revolted in 66-73 BCE and 132-135 CE, during which the Second Temple was destroyed in 70 CE. To this day, Jews pray for the rebuilding of the temple. Even though these revolts reportedly killed more than 580.000 Jewish lives in battle and from disease and hunger, the revolts were unsuccessful. Jewish belligerents were captured and sold as slaves, thus contributing to the growing number of the Jewish Diaspora into the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, including Spain, Southern France, and Southern Italy. The remaining Jews migrated to Galilee because they were barred from Jerusalem in Judea. Many Jews also fled to Mesopotamia, Northern Africa and the North region to France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany. The Roman emperor was so enraged by the revolt that he renamed the Kingdom of Judah as Syria-Palaestina, after the two historical enemies of Israel: Syria and the Philistines.

By 300 CE, three million Jews had settled outside of Judea in the Roman Empire. Reportedly, the Romans and Jews were first allies as Romans took on previously Hellenistic kingdoms. Jews were cited to enjoy equal civic positions under the Romans’ rule, but this seemingly congenial relationship soon diminished.

From 306-337 CE under Constantine the Great, the discrimination against Jews developed when this Roman emperor made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. Adherents to other religions were discriminated against and treated, as Norman Bentwich put it, “more or less like a criminal,” especially the Jews. Under the Romans’ rule, Jews cannot hold positions in government and cannot appear as witnesses against Christians, and cannot marry a Christian. Conversion into Judaism was also prohibited.

Modern day scholars have pointed out that the Jewish practice of brit milah, known as circumcision, created a barrier between Jews and gentiles, even proselytes. Scholars have dubbed this view as ‘Jewish exclusiveness,’ as brit milah more so became an instrument for Jews to distinguish themselves from the gentiles. It served as a mark of their inclusion in the Covenant, and helped them believe that they were the people chosen by God. But it is also important to note that the Romans’ barring and Christian writers’ condemnation of brit milah was what precisely grew this practice’s significance for Jews. Jewish exclusiveness, criticised by even Paul the Apostle, was in fact the result of a strictly-Christian policy, which repressed the practice with, as Bentwich described it, “all the rigour which a jealous and cruel ecclesiastical hierarchy could devise.”

The Rise of Islam and Dhimmis

The death of the Prophet Mohammed triggered the rise of three sequential dynasties, including the Rashidun Caliphate from 632-661 CE. It was during these periods that the Al-Aqsa Mosque was built as an Islamic holy symbol atop the ruins of the Second Temple. The Western Wall, one of the structures left from the Second Temple, was reportedly used as a garbage dump by the Arabs so as to “humiliate the Jews who visited it.” Later on, the term ‘Wailing Wall,’ would be popularised by the British and would often be used synonymously with the term ‘Western Wall,’ though this term is never used by Jews due to its derogatory origin to describe weeping Jews when praying at the Wall.

Throughout Moslem rule, non-Moslems were called dhimmis to differentiate them from Moslems. Translated from the Arabic word meaning ‘protected person,’ the term refers to non-Moslems who enjoy protection to a certain extent under Moslem rule. This perception of protection makes up the bare minimum of religious freedom in the modern sense, as protection for Moslems merely means permitting dhimmis to exercise their religion, albeit far from freely.

Under the Rashidun Caliphate, dhimmis had to abide by a set of regulations established by the Moslem reigning power. Umar I, a powerful Caliph in the Rashidun Dynasty, banned Jews from holding public office. Most notably, the Pact of Umar was the Moslems’ way to preserve their self-identity amidst dhimmis who, at the time, exceeded them in numbers. This need for distinction amongst religions ties in with religious exclusivity, where adherents to monotheistic religions view themselves as the chosen people by God. This entails that other belief systems were subversive at the very least, or inferior at worst.

What is peculiar about the Pact of Umar is that the wording of the pact suggests that it was written by dhimmis themselves, initiating rules such as “we will respect Muslims, move from the places we sit in if they choose to sit in them,” and “we will not imitate their clothing, caps, turbans, sandals, hairstyles, speech, nicknames and title names, or ride on saddles, hang swords on the shoulders, collect weapons of any kind or carry these weapons.” This prohibition from carrying weapons in a period of conquering powers ultimately rendered dhimmis powerless and reliant on Moslems. The intention to distinguish Moslems from non-Moslems was clearly discriminatory in nature, but Jews begrudgingly accepted them in exchange for safety and, in line with religious exclusivism, to separately maintain their own religious identity.

The Umayyad Caliphate’s rule succeeded the Rashidun Dynasty from 661-750 CE. Under this dynasty, dhimmis were subject to pay kharaj, a tax to retain the right to their land, thus making dhimmis merely tenants over their own lands. Dhimmis were also required to pay jizya, a poll tax to be paid individually at a humiliating public ceremony in which dhimmis were struck on the head or nape of the neck. The receipt of jizya is required for dhimmis to travel, and with the religious exclusivity dogma soon became synonymous with a mark of dishonour for non-Moslems in this period. Later on under Ottoman rule, dhimmis’ failure to provide these receipts of jizya could result in imprisonment.

The Jewish-Moslem Relations in the Middle Ages: a Medieval Understanding of Tolerance

The Middle Ages were a particularly dark time for religious tolerance in the modern sense. As concisely written by American scholar Mark R. Cohen, “mono-theistic religions in the Middle Ages were, by nature, mutually intolerant. Adherents of the religion in power considered it their right and duty to treat the others as inferiors rejected by God.” And so this notion of religious exclusivity created a false mask of tolerance, as Cohen put it, “as long as they were allowed to live in security and practice their religion without interference—this was ‘toleration’ in the medieval sense of the word—they were generally content.”

This draconian understanding of tolerance contributed to the view that regarded the early 7th century when the Arab Conquest began as the ‘Golden Age’ of Jewish-Moslem harmony. But the accuracy of this sentiment is a subject of modern debate as this so-called ‘Golden Age’ has been dubbed a mere utopia and was merely the result of comparisonbetween the Jewish-Moslem and Jewish-Christian relations in the Middle Ages. Against the latter, the former may have seemed more tolerant, but Cohen’s concise articulation on the medieval understanding on tolerance above leads to a different conclusion. In fact, dhimmitude, the term coined by Jewish writer Bat Ye’Or to describe Moslem persecutions against Jews and Christians since the rise of Islam, highlighted the inferior legal, social, and economic status of Jews under Moslem rule.

Concerning the dhimmi status, Ye’Or succinctly summed up the situation, “the existence of [the dhimmi] is tolerated under Muslim rule on two main conditions: it must repurchase its right to live on its own land by the payment of a tribute to the Muslim community, and it must accept being humiliated and considered inferior to the Muslim dominant group.”

Scholars are of the opinion that this utopian myth of interfaith harmony, stemming from the Islamic concept of ‘tolerance,’ was weaponised by Moslems in the 20th century against Zionism and Israel in their fight over Palestine. Indeed, the conditions between Jews and Moslems were far from ideal, but the treatment and prejudice they received from Christians in the Middle Ages were arguably even more lamentable.

Christian Crusades and the Birth of Zionism

In late 11th century, Christians in Europe launched several crusades to bring the holy city, Jerusalem, back to the hands of Christians. Jerusalem was a particularly complex location as it is religiously significant for three religions. As Michael Schulson of the Washington Post described it, “at the center of Jerusalem […] sit three major holy sites: the Al-Aqsa mosque, the third holiest site in the world for Muslims; the Western Wall, part of the holiest site in the world for Jews; and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which marks the place where many Christians believe Jesus was crucified, entombed and resurrected.” Despite the pursuit of this revered site, the Christians’ Crusades to take back Jerusalem were far from virtuous and brought about a hellishly grievous age for Jews as they faced massacres, persecutions, forced religious conversions, and eventually, expulsion.

During the Middle Ages, anti-Semitic sentiments and discrimination proliferated around Europe. Jews were accused of kidnapping Christian children and of using their blood for their Passover breads and ritualistic worship; that the disastrous harvest, severe famine and the black plague were all because of the Jews. Libel spread in 1348 Switzerlandaccused Jews of poisoning wells and causing the Black Death, provoking the Black Death pogroms against Jews from 1348 to 1350 in countries such as Spain, Germany, and France. Jews all over Europe were massacred.

Medieval Christians justified these persecutions by believing that the Jewish Diaspora centuries ago was God’s way to punish Jews for rejecting Christ, but they did not stop there. These Christians also believed that it was their duty to continually mistreat the Jews to follow what they considered was God’s will. The Roman Catholic Church even received donations from those deemed incapable to directly participate in the crusade, and this financial payment was made in return for the absolving of sins granted to those who actually went to the crusade in person.

In particular, the Rhineland Massacre of 1096 not only slaughtered Jews, but also forced them to convert to Christianity. Many Jews chose to abide by their faith and eventually took their own lives to avoid baptism. Perhaps most notably, the Spanish Inquisition is the most gruesome corollary of religious exclusivism. The 12th century Spanish Church set up the office of the Inquisition, whose authority includes to punish heresy throughout Europe and whose dominance remained for at least 200 years. The Inquisition tribunal would punish non-Catholics to confinement and torture, where a Clergyman would sit at these proceedings and deliver these punishments. It was in 1288 that mass burning of Jews at the stake first took place in France. These massacres are just two of the numerous persecutions Jews faced in the Middle Ages, and sums up for modern Jews their collective history of suffering.

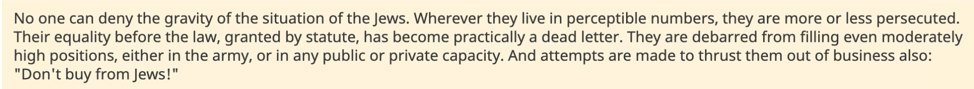

These mass abhorrence and violence in differing places, time, and for varying reasons led the Jews to believe that the only way they could be safe is for them to have their own Jewish State. This idea of creating this State has lingered since its inception in the 1860s by a mass movement who called themselves the Lovers of Zion.

The term ‘Zionism’ was first coined by Astro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl in his 1896 political pamphletwhere he agreed that Jews should have their own country to live peacefully. It was this idea that encouraged massive immigration of Jews into Palestine, their original home before the Babylonian Diaspora, in which lies the holy city of Jerusalem.

The argument for Zionism proved to not be completely baseless, as Jews continued to suffer even decades after Zionism was born. The German Final Solution to exterminate Jews in 1930-1940s Nazi Germany was largely motivated by Hitler’s deluded abstraction of Aryan racial supremacy and the living space / Lebensraum needed for Aryans to thrive. The Nazis’ macabre scheme to realise this extermination included the Kristallnacht, where Jewish synagogues throughout Germany were burnt, and the iniquitous concentration camps, where Jews all over Europe were brought in, forced to work, starved, and killed in gas chambers. Amongst these persecutions and anti-Semitic sentiments throughout the millenia, the systematic killing of Jews in Nazi Germany makes this period one of the most devastating in the Jewish collective history.

Conflicting Promises: the Hussein-McMahon Correspondences and the Balfour Declaration

In 1516, the Ottoman Empire gained control over Palestine and housed Jews, Christians, and Moslems. As the Ottoman lost to Great Britain in World War I and their rule ceased over Palestine, so did this harmony between three religions. It was here that Great Britain concluded two conflicting agreements with both the Arab States and Jews.

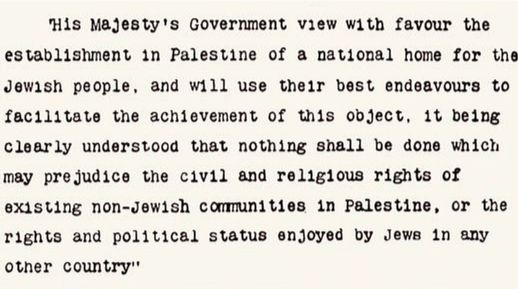

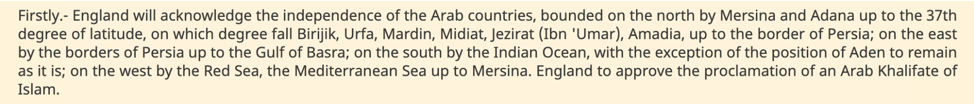

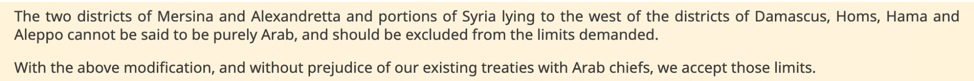

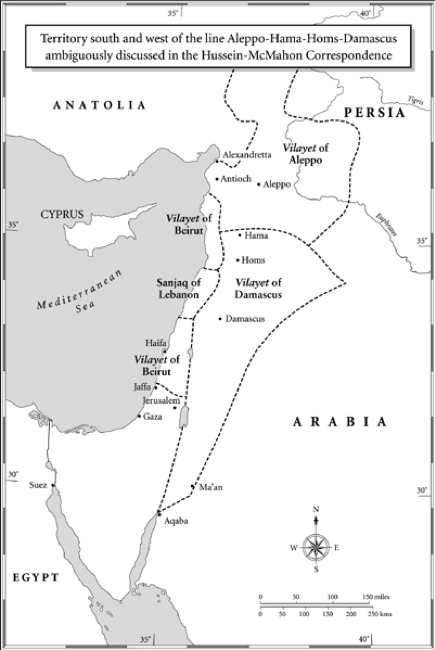

On one hand, to gain support from the Arab States, Britain entered into an agreement through the 1915-1916 Hussein-McMahon Correspondence with Arab. This agreement promised British support of the Arab States’ independence, including territories in Palestine, in exchange for their support for Britain’s victory in the war. On the other hand, Britain also promised Palestine to the Jews in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, later endorsed by the Four Allied Powers in the San Remo Conference of 1920. When Britain won World War I, Palestine officially became Mandatory Palestine under British mandate from 1918 to 1948, and the victory gave effect to these two diverging agreements.

Jewish Influx into Mandatory Palestine and the Entry Ban

The Balfour Declaration triggered a massive influx of Jews into Palestine, repudiated by the Palestinian Arabs. Both agreements effectively mark the beginning of the fight for living space between Arabs and Jews. This discordance would later cause a massive problem and would lead to the modern issue surrounding Israel and Palestine, including the statelessness and displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs through the 1948 Palestinian Exodus.

The influx of Jews into Palestine created conflicting objectives between Zionism and Palestinian Arabs, whose rebellion against this influx led to several riots in Jerusalem. It was also this massive influx of Jews that ultimately led war-weary Britain to issue the 1939 White Paper. This policy paper limited the number of Jews allowed to enter Mandatory Palestine in 1939, and later completely banned Jews from Mandatory Palestine in 1944.

This restriction ignited rebellions against Britain, including campaigns by Jewish paramilitaries Irgun, Lehi, and Haganah. Haganah, in particular, was cooperative with Britain at first, but joined in the rebellion when it became clear that the latter had no intention of immediately establishing a Jewish State. In fact, the 1939 White Paper aimed to establish Palestine as neither a Jewish nor an Arab state, but an independent one in 10 years since its issuance.

The peak of this insurgency was the 1946 attack on the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which served as Britain’s central offices and armed forces headquarters at the time. This attack finally drove Britain to refer this matter to the newly-formed United Nations.

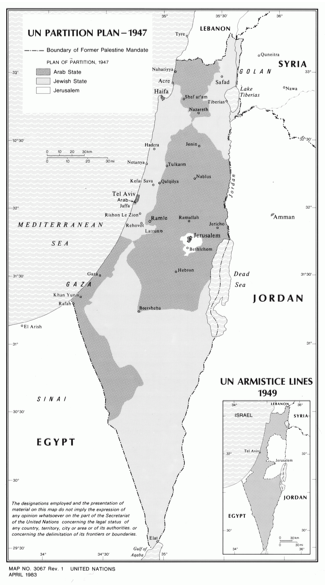

The UN Partition Plan and Civil War

The United Nations addressed this conflict by adopting the UN Partition Plan for Palestine, approved with 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions as Resolution 181(II) on 29 November 1947. This Plan established a Jewish State and an Arab State in Palestine territory, and that these two States would be linked by an economic union. Around 56% of the land of Mandatory Palestine would be given to the Jewish State, and 44% to the Arab States, with Jerusalem as a UN-controlled international zone.

The UN General Assembly also established the Palestine Commission to implement the UN Partition Plan. But in reality, the execution of the plan was far from perfect. The Arab States and Palestinian Arabs never accepted the Plan, and civil war broke out between Palestinian Arabs and Jews in 1947-1949. The Arab Higher Committee (“AHC”) evenexpressed their refusal to recognise the partition plan, and thus refused to assist the Palestine Commission, rendering them helpless in carrying out their mandate “unless adequate means are made available to the Commission for the exercise of its authority.”

In January of 1948, the High Commissioner for Palestine reported that hundreds of trained and armed guerillas from adjacent Arab countries had entered Palestine. These numbers would continue to rise and reportedly increased morale amongst Arabs. But the sentiment was not shared by the Arab

middle class, whose panic was provoked by these increasingly hostile conditions, and a steady exodus has begun for those who could afford to leave Palestine. Britain, Palestine’s Mandatory Power, lost their control over Palestine as attacks against British troops increased. The UN Partition Plan, originally meant to peacefully divide Palestinian territories for Arabs and Jews, further deteriorated the already-hostile situation in the field.

Israel: A Newly Independent State at War

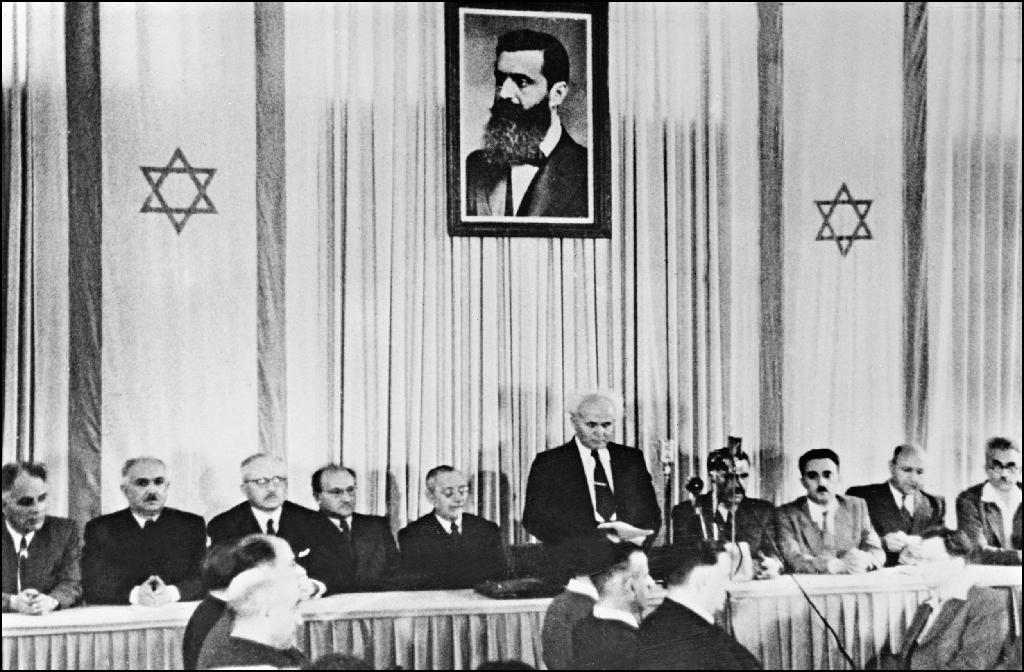

Despite the arduous but unsuccessful journey to implement the UN Partition Plan, Israel declared independence as a Jewish State in May 1948, claiming that this independence had been approved by the UN General Assembly through the partition plan. In its independence declaration, David Ben-Gurion, future Prime Minister of Israel, stated that the State of Israel would ensure social and political rights to all citizens without discrimination of religion, race, or sex.

Israel’s declaration of independence was a tipping-point for the Arabs, who were becoming increasingly frustrated in the absence of significant progress to realise an independent and unified Arab State. On the same day as Israel’s declaration of independence, members of the Arab League and Palestinian Arabs attacked the Jewish State. This attack is now known as the First Arab-Israeli War, where in just a few weeks, Israeli forces faced possible defeat as they were surrounded by the seven Arab League members.

In response to this conflict, the United Nations intervened by initiating a four-week ceasefire and imposed an arms embargo on Israel, which was subsequently ignored when Israel imported heavy armaments from Czechoslovakia instead. After the ceasefire ended, Israel immediately launched a counter attack to occupy Lydda and Ramia, originally allocated by the Partition Plan for Arabs in Palestine.

Israel’s victory in this war preceded its occupation of most of Palestine territory, except for the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, occupied by Egypt and Jordan, respectively. This left hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs displaced and stateless as they fled areas allocated to Jews or occupied by Jewish forces. Historians refer to this occurrence as the 1948 Palestinian Exodus.

The 1948 Palestinian Exodus: Two Nations’ Claims

The First Arab-Israeli War eventually ended in 1949, but not before hostilities between Jews and Arabs intensified in 1948 when Britain was about to leave Mandatory Palestine as decreed in the UN Partition Plan. This led to the 1948 Palestinian Exodus, where some 700.000 Palestinian Arabs fled their homes. But the clear reason behind the Exodus remains debatable to this day. The debate surrounding this issue is incredibly contentious with evidence arising from both parties supporting each argument. Israel and Arab in particular have two contrasting conclusions, each blaming the other for causing the Exodus. Notably, the Deir Yassin Massacre in 1948, reportedly killing more than 100 Palestinian Arabs by Zionist paramilitaries which incited Palestinian Arabs’ panic, were cited by Israel to be no more than propaganda.

Israel claimed that they were not responsible for the 1948 Palestinian Exodus. Quite the opposite, they claimed that they had done everything in their power to stop it and that the Palestinian Arabs fled because they feared the Arab-Israeli War. One evidence backing this claim was that Shabtai Levy, the first Jewish mayor of Haifa, and Abba Hashi, head of the Haifa Workers Council, had tried to stop the panic flight of the Arabs by persuading them to give up the struggle and surrender to the Haganah, a Zionist paramilitary in Mandatory Palestine. Ben-Gurion also supported this effort by sendingGolda Meir, a signatory of the Israeli Declaration of Independence, on a special mission to calm the Arabs and stop them from fleeing their homes. But this mission was unsuccessful, and the Haganah conquered the Arab sections of Haifa, driving the inhabitants away from their home. As a result, the Arabs in Haifa appealed to the British army to provide them with land and sea transport to Acre and Lebanon. Some believe that this British assistance might be understood by some Arabs in Haifa as a ‘signal’ to leave Palestine.

Israel also issued a propaganda stating that it was the Arab leaders who urged Palestinian Arabs to leave their homes and make way for the Arab armies, after which the Arabs would return to share the victory in their own land. Arguably, the most contentious piece of evidence backing this claim is the AHC’s statement which read, “in a very short time the armies of our Arab sister countries will overrun Palestine, attacking from the land, the sea, and the air, and they will settle accounts with the Jews.”

But this argument proved frail from a military logistics point of view. The Arab armies would have needed the food, fuel, transport, manpower, and information supplies from the Palestinian Arabs and would, therefore, not have urged them to leave. Additionally, the recent publication of thousands of documents, including Ben-Gurion’s war diaries, shows no evidence to support Israel’s claims. Quite the contrary to Israel’s argument, recent publications also show that the AHC’s statement was actually intended to stop the mass panic that was causing Palestinian Arabs to abandon their homes. It also served as a warning to the increasing number of Arabs who were willing to accept partition as irreversible. That being said, in reality, the AHC’s statement only increased the Arabs’ panic and flight.

On the other hand, Arab argued differently and rejected all of Israel’s claims. Arab maintained that the AHC, broadcasting from Damascus, demanded the Arabs in Palestine stay put. AHC also asked all Arab officials in Palestine to remain at their post. Further, Azzam Pasha, Secretary of the Arab League, also issued public calls to the Arabs not to leave their homes when it became clear that there was a massive flight of Palestinian Arabs out of Palestine. Arab’s contention was also supported by the Arab government’s decision to allow entry to Arab only for women and children and to send all men of military age back to Palestine. There were also no orders of expulsion nor orders to leave Haifa. These facts contradict Israel’s accusation that the Arab leaders ordered the Exodus. In turn, Arab attributed the 1948 Palestinian Exodus to the Zionists, who always viewed that existing non-Jewish Palestinians should be transferred outside of Palestine.

A multitude of reasons then coalesce as possible reasons behind the 1948 Palestinian Exodus. No conclusive deduction has been determined as the reason why Palestinian Arabs fled their homes in 1948, but this tragedy was repeated in 1967 as a result of the Third Arab-Israeli War, where more than 300.000 Palestinian Arabs fled their homes. To this day, Israel prohibits the return of these Arab refugees into Palestine, their original family homes. Generations of refugees originating from the Exodus now live in camps and are victims of decades-long wars.

One thing remains certain: history has witnessed the chain of events that has led to the Israel-Palestine issue. In particular, the roots of hate cultivated through millennia of persecutions and exile suffered by Jews eventually led to the fight over Palestine, and later the Palestinian Exodus, where thousands of Palestinian Arabs are denied their right to return and are now displaced. The Jews, once an exiled nation and forced out of their homes, have now prevented the return of another nation to their homeland. The fight over living space between Israel and Arabs continues until today.

We sincerely thank Dr. Tristam Pascal Moeliono, S.H., M.H., LL.M., Adrianus Adityo Vito Ramon, S.H., LL.M. (Adv.), and Anna Anindita Nur Pustika, S.H., M.H. for the guidance they have provided as faculty advisors for this series. This is the first article in PILS’ Article Series concerning the issue of Israel and Palestine. The second article in this series will cover the issue of self-determination and the Oslo Peace Accords.