Writer: Nadya Theresia, Ignatius Vito Aquilire

In the last articles in this series, we have examined possible explanations to why and how the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine came about. Through writing, we bear witness to how international ambiguity, hasty politics, and millenia’ worth of hate targeted against Jews contributed to the death and suffering of millions others in the years to come.

But amidst the macabre fight over living space between two nations, arguably the bearers of the most suffering are neither Israel, Palestine, nor any of the Arab States. Indeed, how can we contend otherwise when as many as 5.7 million people now live as refugees, many of whom are descendants of refugees fleeing Palestine in the 1948 Palestinian Exodus. These people have spent all their lives as refugees, with the possibility of returning home dissipating as the conflict between Israel and Palestine continues until today.

From Home to On the Run

The UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (“UNRWA”) defines a Palestine refugee as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine [from] 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as the result of the 1948 conflict.” The 1948 Palestinian Exodus, resulting from mass panic from Arab attack over Israel’s independence, led to the flight of 750,000 Palestinians from their home, effectively becoming refugees.

Israel and Arab each have evidence blaming the other for causing the Exodus, but the exact reason behind the Exodus remains inconclusive. On the one hand, Israel claimed that Palestinians voluntarily left their homes urged by Arab leaders to make way for the Arab armies. Israel’s line or argument relies heavily on the Arab Higher Commitee’s (“AHC”) statement, which reads, “in a very short time the armies of our Arab sister countries will overrun Palestine, attacking from the land, the sea, and the air, and they will settle accounts with the Jews.” On the other hand, Arab contends otherwise, bringing forth their argument that the AHC’s statement was actually intended to encourage Palestinians to stay put. Furthermore, Arab pointed to the fact that Azzam Pasha, Secretary of the Arab League, issued public calls for Arabs to stop their flight and stay where they are.

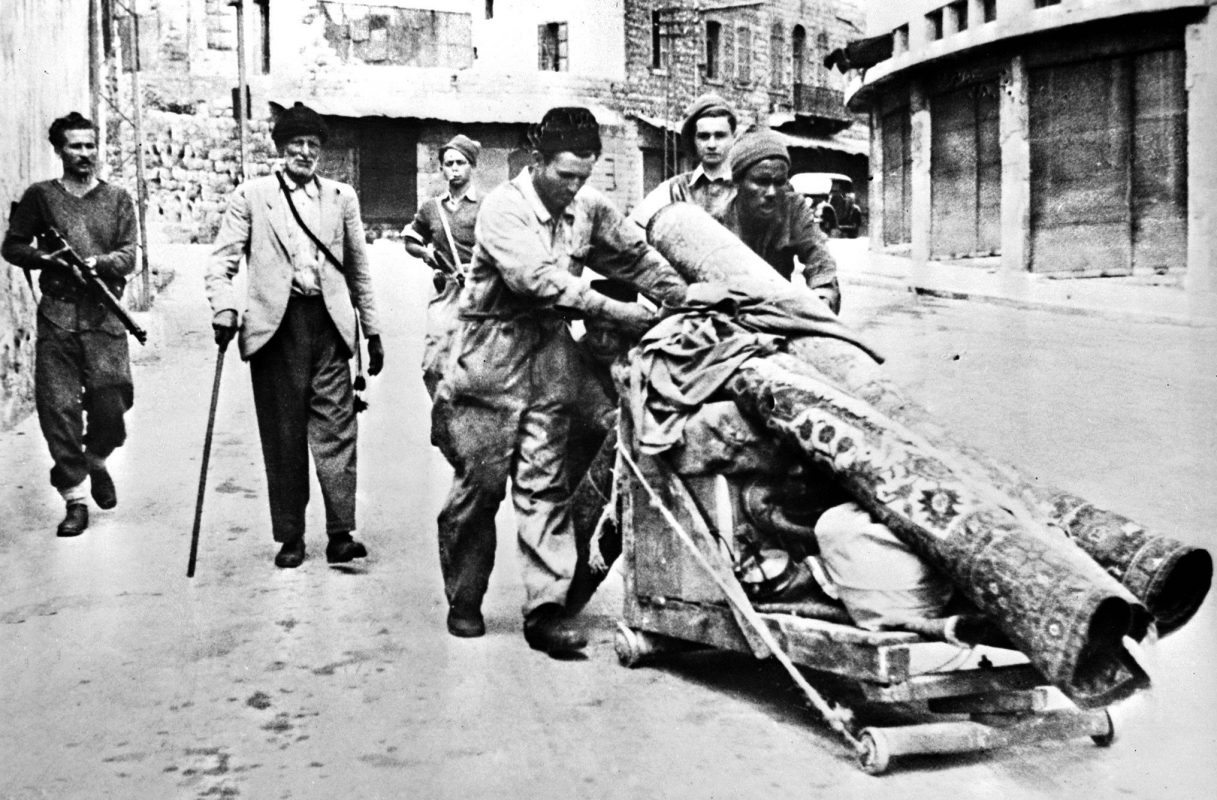

Regardless of what the two nations say, the fact remains that the Palestine refugees fled due to the violence that broke between the two nations merely one day after Israel declared its independence on 14 May 1948. Before Israel declared their independence, Zionists had launched systematic attacks against Palestinian communities through Plan Dalet in April-May 1948 by way of “destruction of villages (setting fire to, blowing up, and planting mines in the debris), especially those population centers which are difficult to control continuously,” and “[…] In the event of resistance, the armed force must be destroyed and the population must be expelled outside the borders of the state.” Arab States, on the other hand, attacked the newly-independent State on 15 May 1948, a day which Palestinians now mournfully call the Nakba Day, meaning ‘the catastrophe’ in Arabic, where hundreds of thousands of Palestinians lost their homes as they fled. The violence that ensued, in which both States had an active role, was what provoked the flight of Palestinians.

The Problem with the Partition Plan

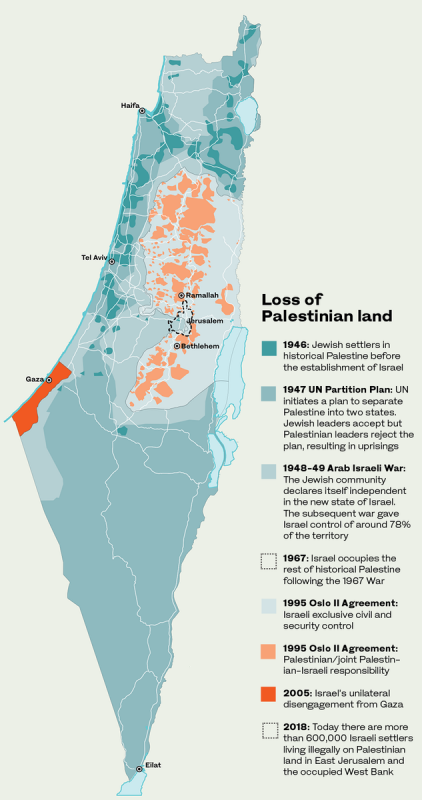

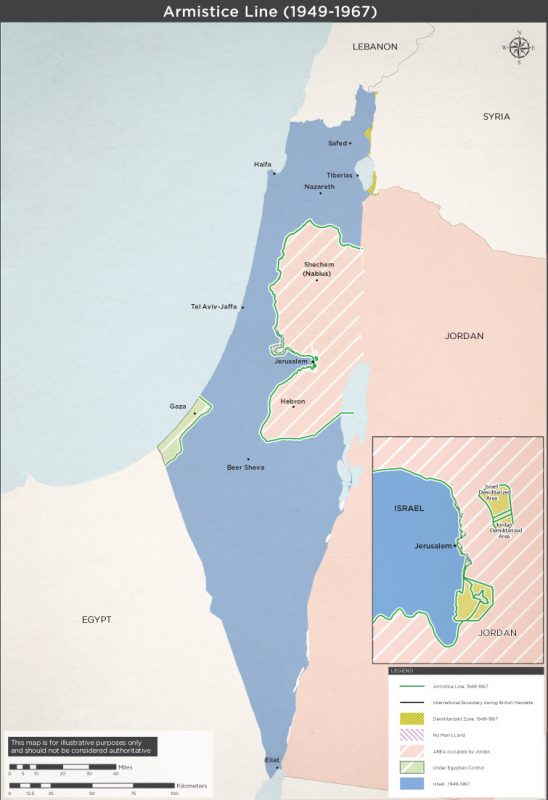

The Israel-Palestine conflict stems from the fight over living space, which was fuelled on by the overly-idealistic and failed UN Partition Plan, aiming for a peaceful territorial separation while in reality achieving the exact opposite. Why was the UN Partition Plan never accepted in the first place? In this regard, Palestinian historian Khalid Walidi explained, “[…] the partition resolution awarded 55.5% of the total area of Palestine to the Jews (most of whom were recent immigrants) who constituted less than a third of the population and who owned less than 7 percent of the land. The Palestinians, on the other hand, who made up over two thirds of the population and who owned the vast bulk of the land, were awarded 45.5% of the country of which they had enjoyed continuous possession for centuries.”

Kalidi furthermore stressed that there was never any consent from Arab States as to the UN Partition Plan itself. It is precisely this lack of consent that ultimately triggered a massive escalation in the Palestinian rebellion against Israel. But partition was favored by Zionists, who had as their objectives the establishment of Jewish sovereignty and the ‘ingathering of the exiles,’ referring to the exiled Jewish Diaspora from old Palestine millenia ago. Arab’s rejection of the partition plan entailed the inevitable use of massive force amidst the Palestinian and Arab resistance, as Kalidi questioned, “how else, in the absence of Palestinian and Arab consent, could the Zionist domain expand from 7% to 55.5% of the land of Palestine assigned to the Jewish state, […] thick with Palestinians?”

Palestine Refugees: Where are They Now?

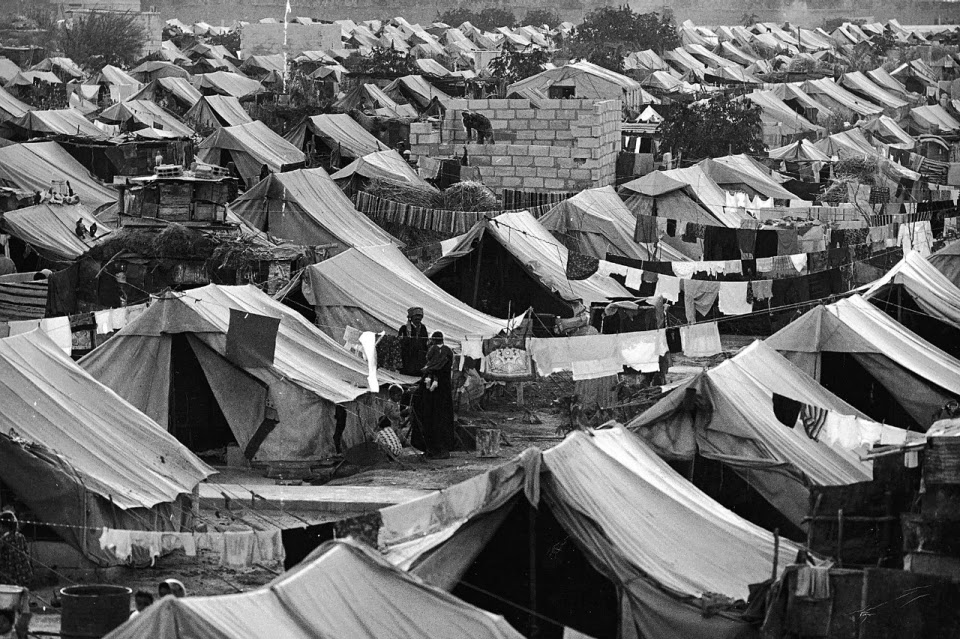

To this day, Israel refuses to allow re-entry into Palestine for Palestine refugees who fled their homes in 1948. Another Palestinian Exodus took place as a result of the 1967 Third Arab-Israelli War, also known as the Six Day War. Out of the 5.7 million registered refugees to the UNRWA, nearly one third of them live in 58 recognised Palestine refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. These registered refugees under the UNRWA live in several refugee camps across several States.

More than 560,000 UNRWA-registered refugees live in Syria, where many have the rights of Syrian citizens, including access to social services provided by the Syrian government. These refugees entered Syria during the 1948 Palestinian Exodus and in 1982 fleeing war-torn Lebanon. But the ongoing conflict in Syria has resulted in the death, injuries, and the displacement of hundreds of vulnerable refugee families. Refugees in Syria face food, water, and electricity shortages, as well as limited access to UNRWA support as the main humanitarian closing Saraya was closed off. Meanwhile, more than two million UNRWA-registered refugees live in Jordan, a portion of whom live in 10 recognized Palestine refugee camps throughout the country.

In Lebanon, more than 475,000 UNRWA-registered refugees live and do not enjoy several rights, including the right to work in as many as 39 professions and cannot own property. The UNRWA reported, “because they are not formally citizens of another State, Palestine refugees are unable to claim the same rights as other foreigners living and working in Lebanon.” Around 45% of the Palestine refugees in Lebanon live across 12 refugee camps in Lebanon, which the UNRWA reported was “[…] dire and characterised by overcrowding, poor housing conditions, unemployment, poverty, and lack of access to justice.”

In the West Bank alone, more than 870.000 UNRWA-registered refugees live, a portion of which across 19 camps. Furthermore, in the Gaza Strip, 1.4 million out of its 2.1 million population are Palestine refugees. The Gaza Strip is now controlled by the HAMAS since their takeover from Israel in 2007. Israel imposed tight blockades on land, air, and sea surrounding Gaza, resulting in deteriorating economic and humanitarian situation there as the blockade effectively barred Palestinians from entering or leaving. The UNRWA reported a 49% unemployment rate in Gaza, one of the highest in the world. Refugees living there face power shortages, overcrowding in camps, and the consequences of intensifying attacks between Israel and Palestine.

Camp Conditions

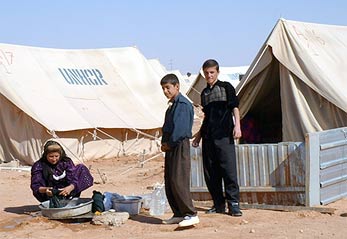

The refugee camps across these States are not UNRWA-administered, though the UNRWA provides humanitarian assistance to the refugees living there, as well as rehabilitation of camp infrastructures. The administration of refugee camps falls under the responsibility of host States, and in this regard, living conditions inside the camps are dire and far from decent. Often the camps are overcrowded, and refugees are not afforded basic infrastructures such as roads, electricity, or sanitation.

Particularly in 2018 Lebanon, refugee camp conditions are made worse as Palestine refugees are not allowed to build or repair property, even within the refugee camps. This entails that Palestine refugees could not repair their homes, schools, or any other facilities even if they are damaged. An attempt to repair it would be illegal, with heavy fines as punishment. Palestine refugees in Lebanon are faced with futures banned from specific fields of work, inability to earn a living due to their nationality, and looming food insecurity amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Palestine refugees in Lebanon have widely been recognised as experiencing the worst conditions, as hopes for a better future are suppressed by Lebanese-imposed restrictions concerning the refugees’ occupation and right to property, rendering them completely reliant to the UNRWA.

In the OPT, refugees have to also bear the brunt of continued armed conflict between Israel and Palestine. Refugees, including pregnant women and children, suffered from asphyxiation due to tear gas, faced difficulties in concentrating for studies, and regularly hid in the basement of their schools in the event of an attack during school hours. A UNRWA staff reported that the ongoing conflict in the OPT was so common that children would sometimes sleep through it, growing accustomed to the noise. Not only refugees, but paramedics doing their job in the OPT also face deadly challenges as they try to rescue people amidst tear gases, live ammunition, and rubber bullets.

The inadequate infrastructure, dismal conditions in the refugee camps, combined with limited access to healthcare, medications, poor hygiene, and lack of proper nutrition have caused Palestinian refugees to face many health challenges. Respiratory infections and pre birth-related complications account for almost 50% of the child death rate in 2007 Palestine. Particularly in Gaza, the rate of stunting (an impaired growth and development of a child) rose above 10% in 2015. Although the UNRWA provides health care to Palestine refugees in camps, many Palestinian refugees often need health care that is not provided by those organizations, often times expensive and therefore, unattainable.

The lack of access to adequate education is no less of an important issue faced by the Palestine refugees. Funding for adequate education is a problem that the UNRWA faces. One instance is in 2018 when the United States cut back $300 million of its funding for the UNRWA’s budget. Furthermore, schools are often overcrowded, and continuing electrical outages deprived the refugees of their electricity for months at a time. These problems directly affect the quantity and quality of study for children refugees, and the lack of education also correlates with the high unemployment rate among Palestine refugees.

In the Absence of Peace

There has been no comprehensive solution to the Palestine refugee problem in decades. The UNRWA was established in December 1949 by the United Nations General Assembly to provide humanitarian relief to the displaced refugees, regardless of nationality, who fled Palestine in the 1948 Palestinian Exodus. The UNRWA’s mandate, originally expected to be short-lived, was repeatedly renewed by the UNGA, and until today has provided 5.7 million refugees with access to health facilities and aid, building schools for child refugees, extending financial services for households as well as entrepreneurs, and many more.

The role of UNRWA itself is to provide aid to affected refugees from the ongoing conflict by addressing the humanitarian and human development needs of the Palestinian refugees. In particular, refugees in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as OPTs frequently meet head on with violence from armed conflicts, restriction of their freedom of movement, the Israeli wall, and house demolitions, which the UNRWA reported to also affect their ability to carry out their work. But to say that the UNRWA is the key solution to end the refugee problem in Palestine would be wrong, as that responsibility falls to the parties to the conflict and the political actors behind it.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees has stated that the refugee problems can only be solved in three different ways: voluntary repatriation, resettlement overseas, and integration with the host community. But Palestine refugees may not be afforded all of these options, as the situation is particularly difficult.

For one, the land into which these refugees have a right to return, Palestine, is now laden with armed conflicts and foreign occupation. Palestinian Arabs have never accepted the territories allocated for them through the UN Partition Plan. These territories are now dominantly under Israeli control as OPTs, oftentimes gripped with violence from armed conflicts between two peoples. Meanwhile, successful repatriation requires physical, legal, and material safety, with full restoration of national protection as the ultimate end to ensure that the return takes place in safety and with dignity. Cooperation between returnees, host, and origin countries is a crucial part of a successful repatriation. Such cooperation between Israel and Palestine is simply nonexistent.

The Palestinian Authority has stated their willingness to accept Palestinian refugees from Iraq, but Israel refused to participate in such a solution. In fact, the UNHCR themselves encouraged Israel in 2003 to allow Palestine refugees from Iraq to enter Gaza and from the Iraqi-Jordanian border in 2006. In both instances, Israel denied re-entry for these refugees. While repatriation remains as one of the fundamental human rights and has in fact been successfully done in the case of Mauritanian refugees from Senegal, and Sri Lankan refugees from India, the situations specific to Israel and Palestine render voluntary repatriation least feasible and realistically unlikely out of all three solutions for Palestine refugees.

Also equally unlikely for Palestine refugees is local integration. Oftentimes, refugees who do not have the possibility to repatriate in the foreseeable future and refugees who have established close links to the host country are considered priorities for local integration. But out of the millions of Palestine refugees, more than 800.000 of them live in the West Bank alone, dominantly under Israeli control. Though the UNHCR estimates that as many as 1.1 million refugees around the world successfully integrated within the local community where they took refuge, this solution is unlikely to work in the context of Palestine refugees as it has failed before.

Resettlement overseas did not prove successful for Palestine refugees, either. In fact, Jordan has refused entry to Palestine refugees from Iraq in 2003, and Syria immediately closed its borders to Palestine refugees after briefly accepting them in Syria. But even though Jordan reportedly granted citizenship to its Palestine refugees population, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (“PLO”) and the Arab League have also rejected local integration and overseas resettlement. In their view, these solutions would only negate the right to return of the refugees, and therefore, rely solely on Israel’s compliance with their own legal obligation to grant the right to return for these refugees.

Most Arab States usually retaliate against PLO’s actions by restricting the rights of all Palestinians or expelling them altogether. One example is Kuwait’s collective expulsion of Palestinians when the PLO voiced support for Saddam Hussein during the 1991 Gulf War. Another example is Libya’s expulsion of several hundred Palestinians as a retaliation to the formation of the Palestinian Authority under the Oslo Accords, after which thousands of Palestinians are forced to relocate to temporary homes and lost their jobs.

The 1951 Refugee Convention and the Protection Gap for Palestine Refugees

The existence of the 1951 Refugee Convention does not automatically mean guaranteed protection for refugees. As regards overseas resettlement, in most Western countries or other non-UNRWA areas, Palestinians must fit into the definition of Article 1(A2) of the 1951 Refugee Convention to be afforded the benefits the convention has to offer, including the established principle of non-refoulement, which has also reached customary status. This principle prohibitsStates from “transfering or removing individuals from their jurisdiction or effective control when there are substantial grounds for believing that the person would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return, including persecution, torture, ill-treatment or other serious human rights violations.”

Having to fit into the definition of Article 1(A2) of the Refugee Convention means that Palestine refugees who seek to resettle overseas must show that they are fleeing their last habitual residence due to well-founded fear of persecution. The problem with this then, as American scholar Susan Akram wrote, “Palestinians cannot claim the original persecution by Israel because they are not Israeli nationals and Israel is not their place of ‘last habitual residence.’” As a result, Palestinians would not qualify as refugees and are not granted the protection owed to them under the Refugee Convention. The final consequence of this gap in the law is that most Palestinians’ claims for refugee status are either denied or entail extreme difficulty.

Indeed, overseas resettlement also needs cooperation from foreign States. Syria in particular has pledged to the Palestinian National Authority that they would accept stranded Palestine refugees at the Iraq-Jordan border, who fled Iraq in 2006 due to intensified killings and death threats in Baghdad.

This 2005 offer departs from Syria’s previous practice of sealing its borders to Palestinians, but in May 2009 Syria again closed their borders to these refugees. And with that, the solutions offered by the UNHCR seems unlikely to solve the Palestine refugee problem.

Middle Ground

Israel has always denied responsibility over the refugee problem, and to-date has never made any significant proposal to repatriate Palestine refugees, specifically persons who are displaced or descendants of the people who fled in the 1948 Palestinian Exodus. To assume responsibility naturally would be the consequence of having caused the Exodus in the first place, and perhaps this is why Israel and Arab have both presented evidence blaming the other to free themselves from fault.

Recent attacks from HAMAS in the Gaza Strip indiscriminately attacking civilians, attacks from Israel in the Gaza Strip, and the lack of accountability by way of investigation of any war crimes point us to the opinion that the finish line in the conflict between Israel and Palestine is still far away. Despite solutions offered by international law by way of the Partition Plan, the Oslo Peace Accords, the ICCPR, the Refugee Convention, and UNSC Resolutions; despite stemming from archaic, albeit significant, origins when Jews were expelled from their own homes and persecuted millennia ago; despite the fact that Arabs were forced to flee their own homes in the 1948 Palestinian Exodus; despite the fact that both peoples have suffered beyond imaginable, in the end, the fight over living space between Jews and Arabs still continues today. The international community unites in the view that ultimately, the conflict between Israel and Palestine could only be solved by and between themselves.

The Case for Peace: Compromise

The biggest criticism of the Oslo Peace Accords was the agreement’s aim to be ‘constructively ambiguous.’ For example, the 5-year interim period established for the withdrawal of Israeli forces did not entail that Israeli settlement building would cease. In fact, Israeli settlers grew from 110.000 in 1993 to 185.000 in 2000, and surpassed 400.000 in 2018. This failure to lay down concrete obligations by and for both parties ultimately led to one’s distrust in the other, contrary to what the Oslo Accords aimed to achieve.

Another example is that Arab leaders never declared to Arab Palestinians that they would have to renounce their claim of their land to settle west of the Green Line as part of the final peace agreement, just as Jews would be expected to renounce their land and settle east of the line. This instilled distrust in both parties that neither were serious in executing the peace accords, as Israelis did not restrict the growth of its occupation by building settlements and Arab Palestinians did not acknowledge the Jews’ contention of their right to Palestine. All the while, Israeli leaders failed to prepare Jerusalem for the inevitable partition into two States’ capital, and Palestinian leaders continued to reject the Jews’ historical, cultural, national, or religious connection to Jerusalem.

Again we witness how ambiguity has contributed to the conflict between Israel and Palestine. First was when Britain made two diverging agreements to Jews and Arab, and now ambiguity in the Oslo Accords have diminished the chance of it succeeding. Moving forward, the need for specifications of rights and obligations and concrete steps towards peace grows more urgent to ensure a successful peace process between two decades-long enemies. But before we venture into the realm of diction and clarity, a foremost need for compromise between two nations is the way for future peaceful relations.

There is no easy way to peace. Mediation and peace agreements between two nations have failed throughout history. We have looked at how both peoples have suffered, how centuries’ worth of hate has added to the modern-day stubbornness of both Israel and Palestine against peaceful co-existence. But it is that same stubbornness that will add fuel to this decades-long fire of violence and war. In the end, the only way to peace is compromise. As Israeli politician and scholar Einat Wilf concisely put it, “Israelis will have to accept the fact that they cannot build settlements all over the West Bank, and Palestinians will have to accept the fact that they cannot settle inside Israel in the name of return. The sooner both sides hear and internalize these simple, cold, hard truths, the sooner we will be able to speak of hope again.”

This is the last article in the PILS Review series concerning the Israel-Palestine issue. We sincerely thank Dr. Tristam Pascal Moeliono, S.H., M.H., LL.M., Adrianus Adityo Vito Ramon, S.H., LL.M. (Adv.), and Anna Anindita Nur Pustika, S.H., M.H. for the guidance they have provided as faculty advisors for this series.